Leiden Canal Pride – Its buried background and history

On September 2nd last year, during the Leiden Pride, queer activists were driven away and enclosed in the morning, then beaten by the police in the afternoon. The following week, the mayor lied about this incident during the same city council meeting where five people spoke out against the police violence. This series of events prompted Leiden activists, including members of Doorbraak who were present at both protests, to investigate the police violence and the underlying decision-making of both the municipality and the police. Why were peaceful LGBTQIA+ activists excluded from a Pride that is also meant to be for them? How could it be that communicating critique was made impossible and that queer people were beaten and arrested at Pride? And how is it possible that afterward, the municipality looks back on that day with satisfaction?

During the Canal Pride Leiden 2023, a group of queer people tried to attach a banner to the Catharinabrug in Leiden. The protest targeted the commercialization of Pride. Expensive boats allowed primarily companies and the municipality to participate in the canal parade, using it as a platform to promote themselves. Attendance to the closing party required the purchase of a ticket, making it inaccessible for those with little money. Gendered, inaccessible toilets made non-binary and disabled LGBTQIA+ individuals feel unwelcome. Although Canal Pride was organized as a celebratory event, it lacked a critical political element, which is the very origin of Pride and remains ever so important. This prompted queer people to take up a banner and add political dissent themselves, but they had to pay for it with violence. The banner was barely unfurled when the police jumped forward to yank it down and started hitting people.

In Dutch/Nederlands

Part 2 in English

Part 3 in English

Meeting Spaces

“Pride is a protest” is a slogan activists have repeatedly brought up at commercial Prides. But what does that actually mean? What are Prides really? Where do they originate? In this article, we provide a brief overview of the history and predecessors of Pride in the Netherlands and the US. It is a history of how queer people made Dutch streets safer for queer expression, and how commerce then opportunistically took advantage of it. Obviously, this article is not a complete history of the LGBTQIA+ movement, and it focuses only on Pink Saturdays and Pride, and even within that, there is much more to tell. The history of the movement is much broader and more diverse than described here.

We use the anachronistic terms “queer” and “LGBTQIA+” in this piece because the terms that the queer movement used for itself until quite recently are very binary. The movement was often referred to as the gay and lesbian movement, or using terms like flikkers (a Dutch slang term for gay men) and potten (a Dutch slang term for lesbians). We choose not to use these distinctions in our wording where we refer to the entire community, so as to avoid erasing people with a non-binary gender identity. Keep in mind that these terms were not used at the time.

World War II was a defining moment for the LGBTQIA+ movement in the Netherlands, as well as in the rest of Europe. Before the rise of the Nazis and their conquest of Europe, there was a small but vibrant queer scene in many European cities, with many meeting places like bars and cafés. (1) Montmartre in Paris is a good example. In Germany, too, where scientists like Magnus Hirschfeld conducted research on what we now call “gender and sexuality.” At that time, there was also a gay rights movement, which, as far as we know, did not demonstrate, but sought to put the emancipation of especially gay men and lesbians on the agenda through books, pamphlets, and films.

The Nazi seizure of power in Germany and the rest of Europe ended much of this vibrant culture. Homophobia and transphobia were part of the Nazi arsenal to instill fear among the German population, and once the Nazis came to power, this hatred could be translated into action. On May 6, 1933, shortly after their take-over of power, the first book burnings took place. One of the targets was Magnus Hirschfeld’s Institute for Sexual Science, causing the loss of years of research and activism. Meeting places and newspapers were also targeted. In this way crucial infrastructure dismantled. Between 3,000 and 9,000 people died in concentration camps because of their sexual orientation, out of the 5,000 to 15,000 who were imprisoned. (G) These figures do not account for individuals who were persecuted for being queer in addition to being Jewish, Roma, Sinti, or labeled as “politically unreliable.” Homosexuality was frequently not the sole reason for persecution but served as an additional basis to target individuals deemed “undesirable.”

Uprising and Protests

After World War II, the survivors were liberated from concentration camps, but only those deemed to have been imprisoned on “unreasonable” grounds by the Allies were actually freed. Others were immediately sent to ‘regular’ prisons. Incidentally, in several Allied countries, such as Great Britain, homosexuality was still illegal. Some of the Allied liberators did not consider homosexuality to fall under “unreasonable grounds”. In England, in 1952, British scientist Alan Turing, who played a crucial role in breaking the German military’s secret code, was subjected to chemical castration due to his homosexuality. This led to his suicide two years later.

It wasn’t until the 1960s that the queer movement was able to organize itself again successfully. In the Netherlands, the first mass demonstration took place on January 21, 1969, at the Binnenhof in The Hague (1). The goal was to abolish Article 248bis of the Penal Code, introduced in 1911. This article made sex between people of the same gender illegal until the age of 21, while the minimum age for sex between people of different genders was 16 (2).

Later that year, a series of events in the US sparked the Prides we know today: the Stonewall uprising. The Stonewall Inn was an LGBTQIA+ meeting place on Christopher Street in New York, popular among drag queens and trans people, many of whom were low-income and people of color, like Marsha P. Johnson. It was one of the spaces where people from this excluded and oppressed community found and supported each other, with practical help and love. On June 28th of that year, the Stonewall Inn became the target of a police raid. This was commonplace at queer meeting places. Officers took pleasure in humiliating the patrons by frisking them, verbally assaulting them, arresting them, and publicly disclosing their names. However, on June 28, 1969, the situation took a different turn. The police were taken by surprise when visitors of the Stonewall Inn fought back and started pelting them with bricks and bottles. In the days and months that followed, this led to more riots, protests, and increasingly public demands for a place in society where queer people would not be persecuted. In June 1970, a Christopher Street Liberation Day was held in San Francisco, Chicago, and New York, commemorating the violence around Stonewall. (3)

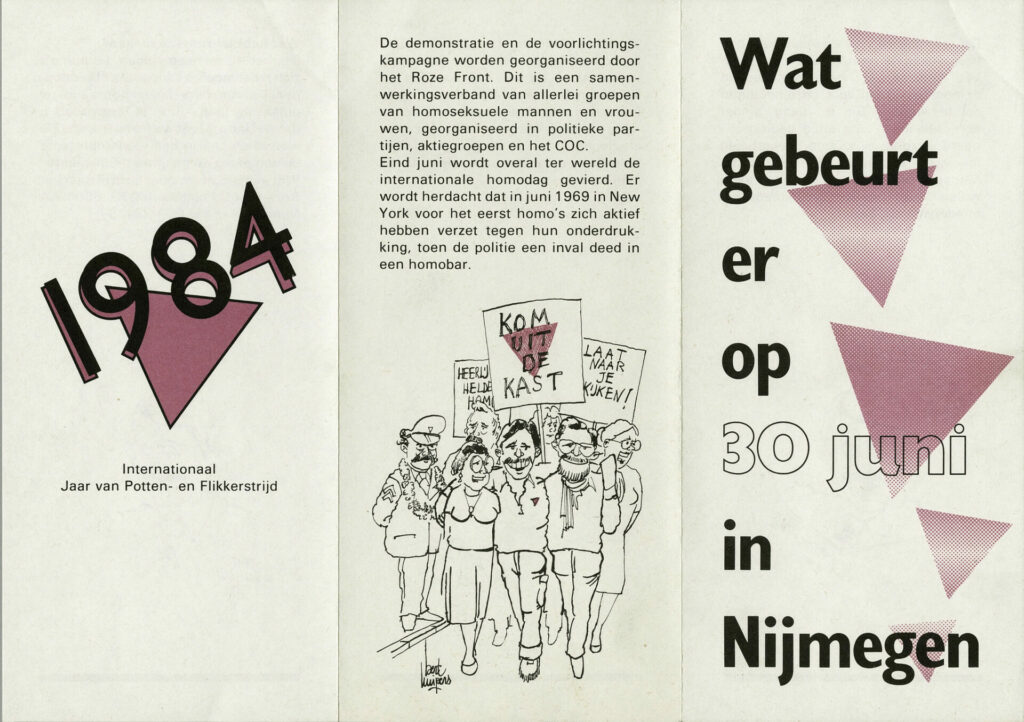

In 1977, another significant event took place in the United States. New anti-discrimination legislation in Miami, which would have prohibited discrimination based on sexuality, prompted the religious right to launch the “Save Our Children” counter campaign. This campaign, one of the first of its kind, succeeded in overturning the legislation in June 1977, to the outrage of the queer community. This sparked protests around the world on Christopher Street Day, even in the Netherlands, organized by the radical feminist International Lesbian Alliance. The march would set the blueprint for those that followed: a daytime march followed by a musical program to celebrate. (4) This was repeated in 1978. And so it happened: once is an incident, twice is a tradition. Starting in 1979, this annual event was named Roze Zaterdag (Pink Saturday). From that year on, it was organized by the Pink Front, a coalition of various LGBTQIA+ organizations.

Demonstration and Celebration

Pink Saturdays had the character of both a demonstration and a celebration. During the daytime demonstrations, people sang, and the atmosphere is often described as convivial. Naturally, the evening parties also had a political character, but they also served as a time for relaxation and liberation for the LGBTQIA+ participants. Each year, it was a reunion of familiar faces hereby forming militant networks to organize the following year’s Roze Zaterdag based on the events that had occurred during the year.

The necessity of this became even clearer in 1982. That year’s Roze Zaterdag took place in Amersfoort and would become a defining moment in the Dutch queer movement. The demonstration had the slogans: “Raised to be straight, daring to be lesbian” and “Raised to be straight, daring to be gay.” The protest was against the way society, despite the partial abolition of legal discrimination, was still heteronormative. (5) Therefore, it was good that cities outside the traditionally progressive Randstad were also visited, such as Den Bosch in 1981 and Amersfoort in 1982. This type of strategy has also been used in recent years by KOZP (Kick Out Zwarte Piet), which demonstrates in places where the racist caricature Black Pete is still part of the Sinterklaas festivities.

From the start, the police and municipality made it difficult for the organizers in Amersfoort. No permission was given for marches, no subsidies were provided for the events, and extending the opening hours of the cultural center De Flint, where the closing party was to be held, was not possible. This last point was important to ensure that partygoers could safely return home after all other nightlife attendees had already done so, but that argument did not prevail. On the day of the event, the demonstration in Amersfoort was attacked by a hostile crowd. Several people were beaten up, thrown into the canal, and some even ended up in hospital. A group got trapped in the community center De Roef and were only allowed to leave in small groups in the evening “for their own safety,” according to the police. The police arrested a few troublemakers but did nothing against the large groups of youths who insulted the attendees in the city park and later at De Flint.

Flora-Tartare

The Roze Front (Pink Front), the organizer of Roze Zaterdag, did not sit idle and, on that very evening, plans were discussed to make the next Pink Saturday a great success. On July 1, 1982, another demonstration took place against the dismissal of the lesbian teacher Toos van den Hurck under the motto “The fight for gay rights continues, especially after Amersfoort.” During this demonstration, the first plans were made to organize Pink Saturday in our own Leiden in 1983. Preparations included self-defense courses and demonstration training to increase the confidence and resilience of the participants.

One tip that was given, intended to give queers more confidence in the face of a potentially hostile audience, but delivered humorously, was: “Choosing one group member and running this rascal through the meat grinder is crucial. It has a preventive effect on the remaining group members, who, if the operation succeeds, will see their buddy neatly divided into portions of Flora-tartare lying on the street on the grass.” (8). The organization also put a lot of effort into educating the people of Leiden and the police, both beforehand in community centers and the media, and on the day itself. (9)

The entire day was organized with solidarity in mind. Buses came from all over the country to Leiden, fostering unity among the demonstrators by singing and cheering from the start. A demonstration newspaper with practical instructions was available for one guilder. Throughout the day, educators were busy handing out pamphlets to passersby. There was also an organizational service, which we would now call “mood management,” mainly ensuring the safety of demonstrators. (10) As always with demonstrations, there were points for improvement afterward: there was no daycare, and the organization relied too heavily on Leiden residents. (11)

Solidarity and Diversity

That a Pride could be safely organized in Leiden at all was thanks to the LGBTQIA+ activists who after Amersfoort worked tirelessly on resilience and education, both on the streets and in politics. Organizing this required close cooperation between various organizations that openly discussed strategy in their publications and other places.

A month after that Pink Saturday, there was unfortunately more violence against an LGBTQIA+ meeting place. This time in Nijmegen, where youths attacked the gay café ’t Bakkertje and its customers during the Vierdaagse (a renowned annual four-day walking event). Once again, the police barely intervened, which provided sufficient reason to hold the 1984 Pink Saturday in Nijmegen. The day was focused on international solidarity and diversity within the movement. One of the speakers, Tieneke Sumter of the Surinamese gay organization SUHO, emphasized the connection between racism and homophobia: “Today it’s the foreigners, but tomorrow it will be the gays.” (12) The Surinamese queer band Oema Soso played in the evening program. (13) This is how activism and celebration are connected; one cannot exist without the other. No celebration without substance, but no joy without celebration.

In 1994, Pink Saturday was held again in Amsterdam, and that year it coincided with EuroPride. EuroPride is still held every year in a different city, and that year it was Amsterdam’s turn. Although the atmosphere was good, the organization ended up in a financial fiasco. A lack of income meant the organization fell into debt, and in 1995 the Pink Front was disbanded.

Historical Significance

On August 3, 1996, something quintessentially Dutch happened: bar owners, albeit from gay venues, wanted to promote Amsterdam as an open, diverse, and welcoming city and together organized the first Amsterdam Pride. This event was explicitly intended only as a celebration, not as a protest or demonstration. It was also inspired by the relative success of EuroPride in Amsterdam two years earlier. That year, EuroPride in Amsterdam concluded with the Pink Saturday floats, but some in the city found them “offensive.” An alternative was needed to put Amsterdam on the map, the entrepreneurs thought, although participants would be required to “behave decently”. This celebration was planned for August, better weather-wise than the end of June but without the historical significance. The demonstration element of Pink Saturdays was not repeated at this Amsterdam Pride, making it solely a party aimed at attracting as many people as possible to Amsterdam.

A comparison can be made with the celebration of May 1st. Originally, this was also a commemoration, namely, of the Chicago workers’ strike for an eight-hour workday that began on May 1, 1886, during which several police officers and workers died in the Haymarket riots. Later that year, prominent union leaders were sentenced to death by the state on flimsy evidence. May 1st is still commemorated in the Netherlands, celebrating the labor rights movement, often with demonstrations. However, Queen’s Day, traditionally celebrated on April 30, overshadowed this commemorative and festive day. Queen’s Day, now King’s Day, is also just a celebration without critical political content and it is also very nationalistic. To this day, the free King’s Day is cited as a reason not to make May 1st a holiday, something that benefits bosses and politicians by preventing workers from demonstrating.

There are also parallels with the recent Canal Pride in Leiden. It was billed as the first Leiden Pride, but of course this is false. Besides the Pink Saturday of 1983, there was also the Queer Pride March in Leiden in 2021. That 2021 Pride was a demonstration and it had a critical and political character. In 2023, the Canal Pride was mainly organized by (hospitality) entrepreneurs, stripped of critical content. Commerce avoids controversy because controversy might drive people [customers] away. The municipality also benefits from such a PR event. In this way, Canal Pride Leiden shed the activist feathers that made a safe celebration possible in 1983 and sparked a Pride in Leiden in 2021. This history is actively denied by Canal Pride by calling itself the “first Pride,” thus erasing the initiatives of 1983 and 2021.

Indebted

Forty years after the Leiden Pink Saturday, Leiden Pride could have been a combative political celebration. A celebration to be yourself, certainly! But also a celebration of the self-grown collective resilience of the queer movement, which over the past decades has single-handedly claimed a place in the Netherlands. A commemoration of the victims of the Nazi regime, of Article 248bis, and of the events in Amersfoort and Nijmegen in the 1980s and all the terrible attacks and hate crimes against those who did not or do not conform to heterosexu al or cisgender norms. To celebrate successes, for example, since 2014, the requirement of sterilization has been abolished for those who wish to undergo gender-affirming surgeries. And a moment to organize for the future: for trans rights now under pressure, against increasing queerphobic and transmisogynistic violence at home and abroad, for refugees whose sexuality and gender experience are questioned by the Immigration and Naturalization Service (IND) and who are deported or threatened with deportation to countries where they are not safe. And more broadly, against the further erosion of freedom and democracy by fascist, liberal, and social-democratic political parties.

Instead, Leiden Pride was a celebration of commerce, where the municipality, businesses, and police had ample space to advertise their supposed diversity and inclusion, without room for dissent. Meanwhile, there were only (wheelchair) inaccessible, binary toilets, and it cost hundreds of euros to participate in the parade with a boat. Even for the closing party, which used to be such an important moment for the community, you had to pay 15 euros. But Nobel in Leiden did achieve what could not be done at De Flint in Amersfoort at the time: the Nobel was allowed to stay open until three in the morning. For all this, the Canal Pride Leiden foundation received an entrepreneurial award. But Canal Pride should not be a business, because this Pride (and all others) is indebted to activists: they stand on their shoulders!

And the festivity was maintained through enforcement in September 2023. After we, resilient queer individuals and sympathizers, defended a drag queen story hour by Dina Diamond from fascists in the morning, we attempted to affix anti-capitalist banners critiquing pinkwashing to the Catharinabrug in the afternoon, where the boats would pass by. This was immediately met with violence by the police: the police, who in 1982 did nothing to protect LGBTQIA+ people from right-wing violence and had to be trained by the queer movement after Amersfoort, were quick to silence political expressions of queers in 2023. This included, among other actions, beating them into a ‘demonstration area.’ Open politics during the Leiden Canal Pride, according to the municipality and its strong arm, belonged in a yellow-bordered area of a few square meters, surrounded by a line of baton-trigger-happy police officers, and without sound amplification. The safe Pride forty years ago had been made possible by the self-defense and training of political LGBTQIA+ individuals.

Pontifical Part

A large demonstration march is again held at Amsterdam Pride since 2012. [De tijdlijn in het origineel is me niet helemaal duidelijk] Since 2023, the organization of the entire theme week has been split between two entities: the Pride Walk and other events are organized by Queer Amsterdam, a coalition of various queer organizations with a political approach, while the rest of the week is handled by the Stichting Pride Amsterdam. This brought politics back into Pride. This year, protests were held against Pride sponsor Booking.com for renting houses in Israeli-occupied Palestinian territory. Queer Rotterdam and Niet Normaal* (Not Normal*) in Utrecht have previously organized radical blocks during Pride or alternative Pride demonstrations. Last weekend at the Canal Pride in Utrecht, there were banners for Palestine, which were hung on bridges.

A Pride is a celebration. A celebration in which the city turns pink, and space is claimed by the LGBTQIA+ movement. It is a celebration of liberation from the stifling boxes that are still the norm. For all people who belong to the rainbow family, it is a celebration of being able to be [ik vond ‘being allowed to’ een beetje autoritair aandoen voor ‘mogen zijn’]. But a good Pride must also be diverse, inclusive, and political, with room for multiplicity, critique, and depth. Especially for those who are still the most marginalized. The mix of politics and celebration was the strength of the Pink Saturdays. And it is precisely the activism surrounding Pride that must continue. That is why it is so intolerable when the municipality and police silence critical voices from the community, push and beat queer people aside, stifle their demonstration rights, and exclude them from Pride. Taking Pride away from them.

On September 7, 2024, there will be a new Pride in Leiden. In 2024 and beyond, we hope to see not only political blocks that are an integral part of Pride but also attention given to the struggles and history that underpin Pride. Because Pride started as a protest and it is still a protest. Down with heteronormativity and coercive gender norms, and down with capitalism, racism, and patriarchy.

Mariët van Bommel and Bo Salomons

In parts 2 and 3 of this series we discuss the course of Leiden Pride last year and the research into the authorities’ decision-making.

Special thanks to Dr. Noah Littel for providing large amounts of archival material from which we could draw. Noah shared a selection of archival material encountered during their archival research. The shared material consists of articles from the magazine Sek included in the archive of the Stichting Roze Front (Foundation Pink Front). Stichting Roze Front was founded in 1979 to organize the annual gay demonstration (Pink Saturday). It was a collaboration of Dutch gay and lesbian groups. This archive is part of the collection of IHLIA LGBTI Heritage and stored at the International Institute of Social History in Amsterdam. (Archive Stichting Roze Front, collection number ARCH03231, box 2, folder 2. Storage location: IHLIA collection, at the International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam). The magazine Sek is also available in the magazine collection of IHLIA LGBTI Heritage.

Notes

- 1. Rob Pistor, “Roze Front: Tien jaar na Stonewall: 30 juni demonstratie Amsterdam”, Sek: Tien jaar na Stonewall 1979:6 (1979). Archief Stichting Roze Front, collectionnumber ARCH03231, doos 2, map 2. Stired at: Collectie IHLIA, at the Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis, Amsterdam (From now on: Archief Roze Front).

- 2. Rob Pistor, “Roze Front: Tien jaar na Stonewall: 30 juni demonstratie Amsterdam”, Sek: Tien jaar na Stonewall 1979:6 (1979). Archief Stichting Roze Front.

- 3. Han van Delden, “Stonewall Inn vanavond open”, Sek: Tien jaar na Stonewall 1979:6 (1979) Archief Roze Front.

- 4. Fons Derrez, red., “Roze week ’82: Allemaal naar Amersfoort!”, Sek 1982:6 (1982) Archief Roze Front.

- 5. F. Derrez & H. Hoogerbrug, “Allemaal naar Amersfoort!”, Sek: Amersfoort; de kei, de kater, de kick 1982:6 (1982) Archief Roze Front.

- 6. Sek: Amersfoort; de kei, de kater, de kick 1982:7 (1982) Archief Roze Front.

- 7. Fons Derrez, red. “Tot ziens in een feestelijk Leiden”, Sek: Homo’s en weerbaarheid 1983:7 (1983) Archief Roze Front.

- 8. Peter Schook, “Het antwoord op agressie is weerbaarheid”, Sek: Homo’s en weerbaarheid 1983:7 (1983) Archief Roze Front.

- 9. Derrez, “Tot ziens in een feestelijk Leiden.”

- 10. Derrez, “Tot ziens in een feestelijk Leiden.”

- 11. Fons Derrez, red., “7000 flikkers en potten zingend door feestelijk Leiden…” Sek: Leiden in Lust: een beeldverslag 1983:8 (1983) Archief Roze Front.

- 12. Jehoeda Sofer, Aaf Tiems, “Op herhaling in Nijmegen”, Sek: 8000 flikkers en potten in Nijmegen 1984:7 (1984) Archief Roze Front.

- 13. Idem.