“I want to feel free without needing to be brave” – An account of a train journey to Istanbul to join the International Women’s Day demonstration

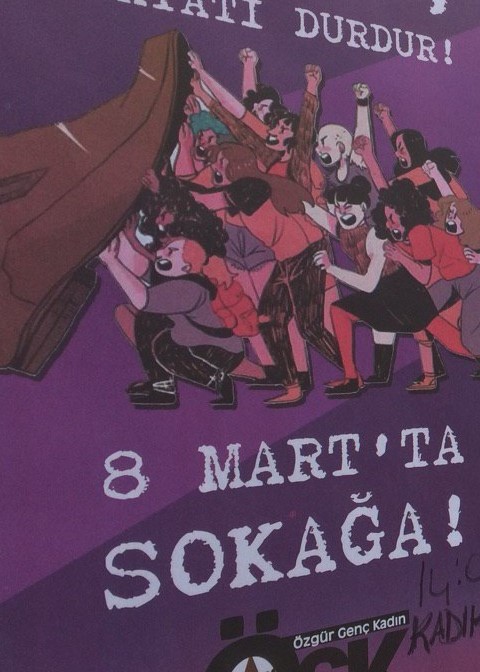

“Jump, jump!”, it sounds all around us. “Jump!” So we jump, as high as we can, like other women are doing in the streets of Istanbul. It is the night of 8 March 2020, International Women’s Day. Thousands of women gathered to reclaim the streets of Istanbul.

During that night, we – all the women of the night march – used our voices and whistles to make as much noise as possible. Istanbul should hear how women claim the streets, should feel how the women resist the police, teargas and rubber bullets, and should see how women defend their rights. It was not the first time women claimed the streets of Istanbul. It won’t be the last time.

This story is the personal account of our, Sara’s and Ronja’s, journey, from the Netherlands to Istanbul, and tells how we ended up jumping during the night walk on International Women’s Day.

Even a dog needs a passport

The idea to join the Women’s Day in Turkey arose last year after Sara had visited her friend Melek in Istanbul. While in Istanbul Sara had attempted to take part in the 8th of March demonstration. Back in the Netherlands the two of us (Ronja and Sara) met for a coffee and chatted about Istanbul. Even the small amount Sara had seen of the 8th of March demonstration was inspiring. We hatched the plan to return to Istanbul to participate together with Melek in the Women’s Day demonstration.

Hier kun je een Nederlandse vertaling lezen. Here you can read a Dutch translation.

But then corona virus started spreading through Western Europe and our travel plans became more doubtful. After several anxious phone calls we finally set of. Despite some small setbacks and a few sleepless nights, our journey went smoothly, even the corona virus held off until after our return.

We travelled from Netherlands taking progressively slower trains through Austria, Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria and finally into Turkey. At each border town the train stopped and a group of surly men bordered the train to demand our passports. We handed over our Dutch and German ID cards. The men dispersed into offices taking our precious documents with them. After an anxious half an hour the men reappeared, ID cards in hand, and the train set off across the border.

The only border at which we had to leave the comfort of our sleeper train couchette was when we left the EU and entered Turkey. In Kapikule, the first stop after the Bulgarian-Turkish border, the officer handed over a flimsy piece of paper with a date stamped on it. “Don’t lose this”, he growled. This was seemingly the only sentence the many officials at the tiny border station could utter.

Travelling such a distance on just our ID cards and without a visa was something which would be impossible for Melek. She needs to submit a large pile of forms and evidence every time she wishes to travel to Europe. Melek eloquently summed up how unusual it was to be able to travel so far with only an ID card. She pointed to the blue booklet piled up with her pet’s comb, toys and treats: “Even a dog needs a passport”, she complained.

T.coffee and smuggled tea

During our time in Istanbul we stayed at Melek’s place in Kadiköy on the Asian side of the city. Our friend gave us a warm welcome and opened her lovely home to us. She also showed us her favorite places in Kadiköy. Most of the café’s we visited were leftist in their politics. There were several clues that this was the case, Melek pointed these out to us. They were not offering Turkish Coffee. Drinking Turkish Coffee in a café in Istanbul is just a normal thing to do, we thought. But it’s all in the name. When we had a closer look at the menu we couldn’t find Turkish Coffee. Instead they offered T. Kahve (T. Coffee). In none of those leftist café’s they were using the word Turkish but shortened it to “T”.

When it comes to tea, there is also an interesting story to tell. Tea is one of the other common things to drink, we assumed. Thanks to Melek we know now that you can’t just order a tea in a Kurdish café. They will ask you if you want to have normal tea or smuggled tea. Kaçak Çay – or smuggled tea – is smuggled from Iraq into Turkey.i And guess what, we smuggled it back to the Netherlands.

One last question

The day before International Women’s Day Melek had invited some friends to her flat to discuss the demonstration on Sunday. We spent the whole evening with those wonderful women: Canan, a woman who shared a lot with us but didn’t dare to tell her parents about her lesbian relationship; Eda, the partner of Canan, who also kept their relationship secret, and Iida who had just finished her degree and preparing her van to travel to Europe.

We drank beer, ate the delicious lentil köfte Melek had prepared and talked into the small hours. It felt like we were sharing much more than just food and conversation. New friendships were forming.

With our new friends we spoke about our experiences in daily life and shared several stories about political actions. We still remember the story, Canan told us, about a woman at the university in Istanbul who was confronted with unwanted sexual attention by another student. As a reaction to that other female students spread a picture of the man around the campus to make this harassment public. They also “visited” his lecture to blame and shame him.

But stories about incredible police violence also passed by. During an action, our new friends told us, the police attacked the women, pulled their hair and threw them down the stairs. At another action our friends were forced to use their own bodies as an “airbag”. The first woman lying on the ground catches the rest of the following bodies. Listening to those stories I, Ronja, wasn’t so sure anymore if I could handle being arrested.

And every time we thought we had learned enough, we still had just one last question. But we were not the only ones asking questions. In fact Canan had an abundance of them and gave us plenty to think about. We talked about our families, and Melek, Iida, Eda and Canan described how young people felt under pressure to marry. Then it turned into a question to us: “What are your families like about marriage?” As I, Sara, described the attitudes of my happily unmarried parents I once again felt the privilege of coming from Western Europe. Given this was it right that I participate in the demo? It was International Women’s Day, but is this struggle really international? Was I inconveniencing our new friends by tagging along for this demonstration?

We don’t have answers to these questions, but as our new friends assured us that it was fine if we come along (with the caveat that they didn’t really know if we as foreigners were in more or less danger if arrested) we decided to go.

8 March 2020

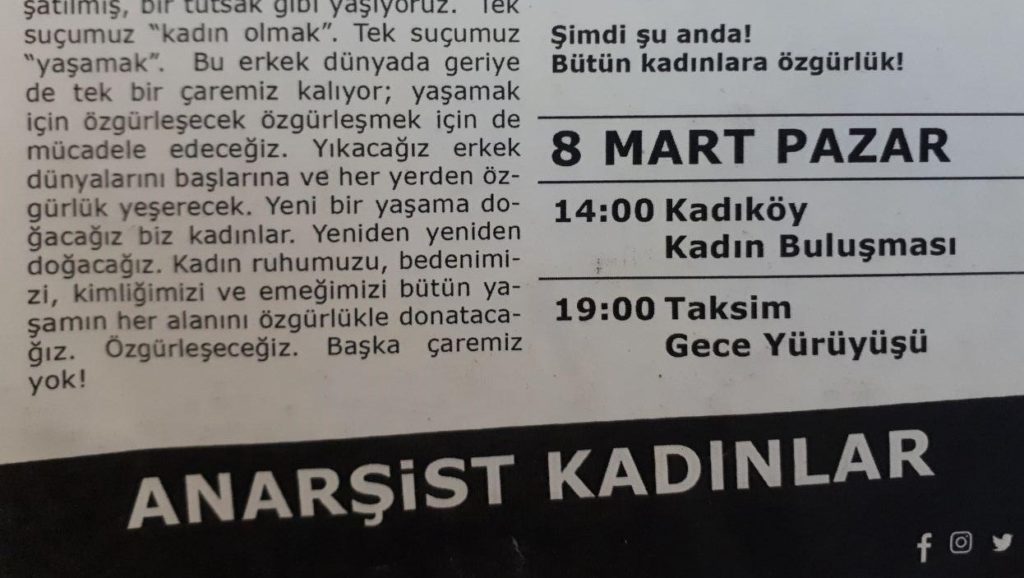

With Melek, we made a plan for the day. We would first attend a rally in Kadiköy and then meet our new friends from the night before and head to the main demonstration at the Taksim square.

At 2pm the three of us (Melek, Ronja and Sara) went to the ferry terminal in Kadiköy.

There, hundreds of women came together for Women’s Day, protesting male violence against women and inequality. You could see a wide range of women: young, old, religious, Turkish, Kurdish, anarchists, socialists, liberals, etc. The place was covered with flags and banners.

Melek did a great job translating for us as series of women from the diverse groups represented at the rally took to the stage. Each speech was followed by slogans from the crowd or by music from bands like the female protest band BandSista.ii All the speeches and slogans had at least one thing in common: LGBT and Women’s Rights.

During the demonstration a poster with just the number 6284 written on it drew our attention. Later, on our way home, we made use of the wifi in our hostel in Sofia to look up what this meant. It turns out that this number referred to a law on preventing and combatting violence against women.iii But unfortunately it seems not to be having much effect. Listening to Melek and her friends’ stories and to the speeches during the demo we heard how in Turkey women are still subjected to violence.

Before departing Ronja had done some research and found reports by several national and International NGO’s which confirm this. Their message is clear: in Turkey women face discrimination and violence, particularly femicide.iv For example, last year 474 women were murdered by men.v This is more than one woman a day. Emine Bulut, 38 years old, is one of them. She was stabbed to death in front of her daughter by her ex-husband. This brutal femicide sparked outrage across the country.vi

From reading these reports we also learn that the government’s response to these attacks is lacking. The governmental orchestrated protection of women currently focuses on women only as part of the family, not as individuals. NGO’s are pointing out the development towards only discussing women’s rights as long as women are defined through conservative heterosexual family values.vii At the Women’s Day demonstration this was also a topic. Women were carrying posters referring to women as individuals in their own right: “We are not a family, we are women.”

After the manifestation in Kadiköy the idea was to travel by public transport to the Taksim square and continue the protest there. At 3pm we took the ferry across the sea to the European side of Istanbul.

Everywhere is Taksim

The Women’s Day demonstration would start at 7pm at Taksim square. As we walked towards the square the always knowledgeable Melek told us about its significance to the Turkish left. Located in a historically diverse working class neighborhood, Taksim has been at the center of political struggle in Istanbul for many years. It is the favored meeting place for demonstrations and was at the center of the Gezi park protests of 2013.

But, Melek told us, recent years have seen a concerted effort to change the character of the square. A large mosque has been built in an attempt to change Taksim from a space for secular politics to a religious space and the diverse area around Taksim square has been rapidly gentrifying.

On our way to Taksim we met up with our new friends from the night before: Canan, Eda and Iida. Getting to Taksim was not easy that day. First we tried the metro. It was closed. So we walked, as we did so we saw more and more police. Roads were blocked by barriers, water cannons and armed police. There was no way we were getting to Taksim. After walking for more than two hours, we settled down in a cafe in a side street to Taksim.

We were amazed at the bravery of our Istanbulite friends, they seem to have no doubts about marking Women’s Day at Taksim square. But for us it was time to leave. Seeing how desperate the police were to keep us from Taksim has worn out our nerves. The stories we heard from our new friends in the café didn’t help. We heard how willing the police are to use water cannons, rubber bullets and many different “flavors” of tear gas.

Our friends headed towards the demonstration to Taksim square and we sat on a park bench and discussed our fear and our deep respect for the women who were marching. We later heard that in the time we had been sitting in the park there had been 34 arrests – women dragged off by 3 officers while their colleagues taunted and beat them.viii

While thousands of women turned away from the still blocked Taksim square and start to march towards the sea, at our park bench we made a decision. We will head back towards the square – just to have a look. Map in hand we played the lost tourist and followed the noise towards the demonstration. When we found the women we had no choice but to join them.

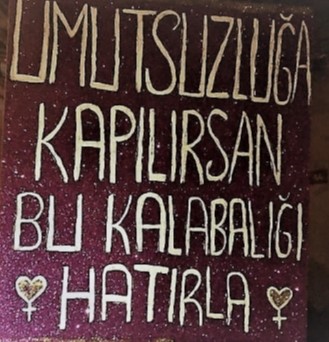

The energy was extraordinary. Women were chanting, shouting and waving banners. Two of them stick in mind: “Wherever I go I want to feel free, without needing to be brave”, a reference to sad fact of violence against women in Turkey, but which could just as easily refer to the bravery needed to claim the freedom to march and protest. The second needs no explanation, it said simply: “If you are desperate, remember this crowd”. As we passed people leaned out of windows to wave, we saw one little girl waving happily at us.

Down by the sea the demonstration dispersed and our little group headed back to the ferry. But the evening wasn’t over. Outside the ferry terminal a large circle of women was dancing and as the ferry left Europe behind women started singing and changing once again. That is until people called for quiet as a middle aged woman got up to talk. She was Hasbiye Günaçti.ix “A famous activist”, our friends whispered to us. Günaçti addressed the men on the ferry and asked them to stay away from feminist actions. They have a role – to challenge other men who are violent towards women – but in feminist actions it is important for women’s own voices to be heard.

We arrived back at the Asian side of Istanbul, tired but happy and empowered. We said goodbye to Canan, Eda and Iida and went for a few drinks with Melek in our favorite Kurdish cafe (serving T. Coffee and smuggled tea, of course) and then bed. Tomorrow we begin our long journey back to the Netherlands via Bulgaria, Serbia, Croatia, Slovenia, Austria and Germany.

To the brave women of Istanbul

We are extremely grateful to all the women involved in organizing and participating in the 8th of March rally and demonstration in Istanbul.x They should know that the movement they are part of is large, powerful, and valuable (or at least that’s how it seemed to us). We also want to thank Melek and her friends, Canan, Eda and Iida, for allowing us to join them for the International Women’s Day march and for educating us about the women’s movement in Turkey.

Reflecting back on the day we note several things. First, we want to mention the diversity of the rally and the demonstration. It did not seem to represent the leftist sub culture or clique one so often sees in European activists circles – though we do have to admit that international women’s day is often an exception to this. The crowd in Istanbul seemed to be a diverse crowd of women who wanted to assert their right to the city and the night.

We were also impressed by the flexibility of the women involved in the demo. The aim was to demonstrate on Taksim square, when this proved impossible a new plan was quickly made to march through streets with a far smaller police presence. By asserting and showing that everywhere could be Taksim, it became impossible to close down resistance completely.

Finally, we must note that the way the large number of women reacted to the police threat was simply very brave. The numbers out on the street in the face of an overwhelming police presence required the bravery of many thousands of ordinary women. Bravery which should not be necessary, but which was nevertheless there.

Sara and Ronja

Notes

i “Travellers wanting to cross from Iraq into Turkey stand a better chance of making it if they embrace tea smuggling”, The Times, 6 November 2017.

ii BandSista are the women members of the collective Bandista along with their women comrades, who used the name BandSista.

iii Burcu Karakaş, “Femicide in Turkey: What’s lacking is political will“, Middle East Institute, 18 December 2019.

iv Dilek Sen, “Feminismus in der Türkei, Aufstand der Frauen“, TAZ, 5 March 2020, and “Country Report on Human Rights Practices 2019 – Turkey“, USDOS – US Department of State, 11 march 2020.

v “Being a woman in Turkey: ‘No justice, no equality, no safety!'”, Ahval News, 8 March 2020.

vi Carolina Drüten, “Frauen und Männer gleichstellen? ‘Das ist gegen die Natur'”; Die Welt, 1 September 2019; Toon Beemsterboer, “Mannen slaan omdat vrouwen provoceren, zeggen veel rechters”, NRC Handelsblad, 30 Augustus 2019; “Turkey bans Istanbul International Women’s Day rally for second year”, The New Arab, 8 March 2020.

vii “Shadow NGO Report on Turkey’s Seventh Periodic Report to The Committee on The Elimination of Discrimination Against Women”, The Executiv Committee for NGO Forum on CEDAW -Turkey, July 2016.

viii Confirmed by the World Organization Against Torture: “Turkey: No Justification for disproportionate use of force against peaceful women’s rights march”, OMCT, World Organization Against Torture, 13 March 2020.

ix Irfan Aktan, “18 Frauen, die man kennen sollte”, Taz.gazate, 8 March 2019.

x We would also like to thank Toby and Caya for proofreading this article and Özden for translating all the banners in our photos and by doing so making an incredibly slow Serbian train ride pass more quickly.