Why is Greta unsafe on the stage of the Climate March?

On Sunday, November 12, Greta Thunberg, while on the stage of the Climate March, was besieged by a white man wearing a bright green jacket. He enters the stage, bypasses security, grabs Greta’s microphone and says, “I come here for a climate demonstration, not a political view.” No one from the climate march organization takes any action, leaving it up to the activists on stage to remove the man from it. Where did he get the nerve to silence a young woman, the most well-known young woman in the climate movement at that? Well, he was able to copy the behavior from the climate march organization, which shortly before had turned off the microphone of a woman because her message about her people experiencing genocide and ecocide had not, according to them, been “connective”. In other words: monkey see, monkey do.

Dutch original of this article.

Dieser Text auf Deutsch

Isn’t that too short-sighted? If we look at this event as an incident, it may seem ‘coincidental’. Now the fact of the matter is that I have been a climate justice activist for 14 years in a country where the climate movement did not emerge from justice struggles, but with a history of green NGOs working for the environment within a very narrow framework, which is concerned with emissions molecules and statistics rather than the struggles of displaced people who have already lost their families due to invading forces looting land or polluting it to the point of illness and death. In the struggle for justice, main concerns are health, care, solidarity and putting an end to invasion (this includes military and political violence and violence committed by multinationals). The space Indigenous peoples can take up in bright green NGOs is restricted to the frame of the white savior, a rescuing or concerned citizen who has to make the right decisions and who refuses to look into the militarism and colonialism ruining the earth today and strips agency away from others.

Now, the fact of the matter is that for 14 years my experience has been that “now is not the time” to talk about climate racism, which actually provides the political-historical perspective on how some populations are structurally politically sacrificed for the expansionist impulses of powerful military states, losing land, water, resources, biodiversity and community through the terror of the power that considers itself superior.

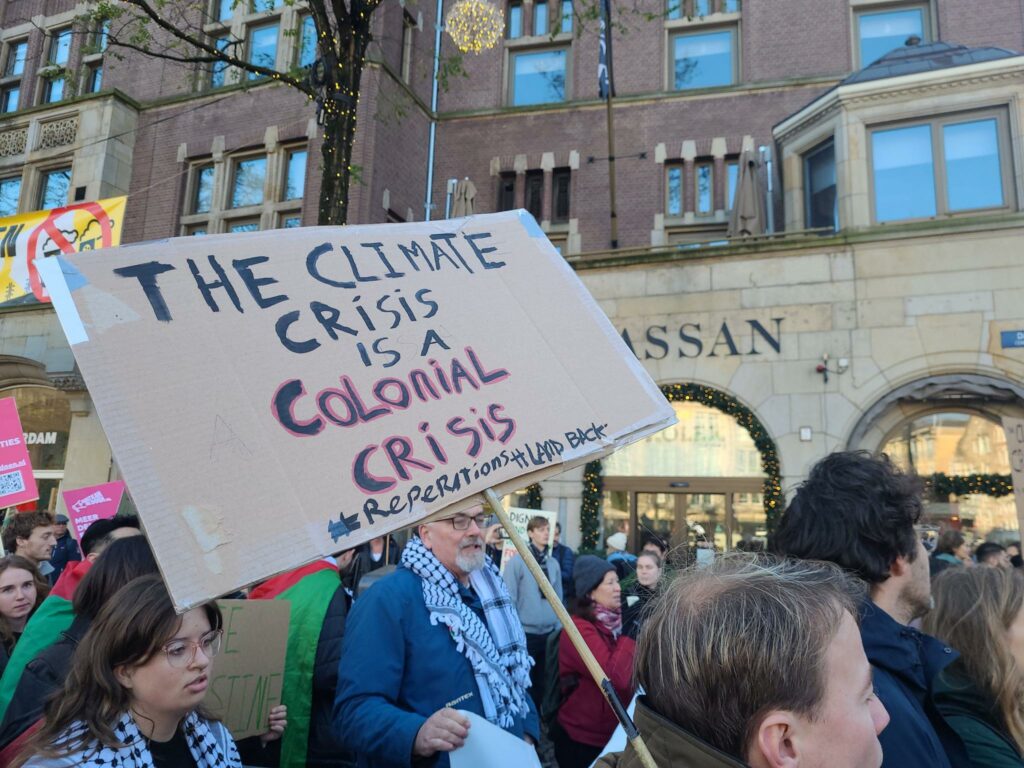

Now, the fact of the matter is that for 14 years already I have been accumulating memories of systemic exclusion of Indigenous voices, their view on the climate crisis and the politics that created it. Let me outline a framework so that we are no longer talking about a shocking “incident,” but about a gatekeeping racist norm that has been silencing Indigenous peoples for years, or that has tried to appropriate them in a way in which the pleasure and well-being of those who do not experience displacement from their habitat is more important than the lives of those who do get deprived of their land and water and life. The climate march has turned a blind eye for years, not only silencing the microphone of a Palestinian speaking about the erasure of her people, but also discriminating against an entire bloc of organizations that are committed to climate justice out of solidarity with Palestine. The bloc had correctly registered via the form on the climate march website, but were told in euphemistic terms that they were unwelcome. More on this later, but first, a historical perspective on the Dutch climate march.

I have little recollection of my first climate manifestation in the Netherlands; it felt like a misplaced party; there was music and people saying something about CO2 as if it had just fallen out of the sky and didn’t have a history of hundreds of years of imperialism escalated by fossil warfare. English nationalism in the heyday of their colonial empire that covered 25 percent of the earth’s surface led to statements like “Coal itself is an Englishman.” Coal-fueled warships were not dependent on the wind, which provided military advantage by giving the coal warship more control over maneuvering on the battlefield. Due to colonialism, an enormous amount of fossil fuels were stolen from colonies. The growth of the Dutch predecessor of Shell was accelerated by the merging of power. Their first board included a big shot from the Royal Dutch East Indies Army (KNIL), the director of the Chamber of Commerce and politicians from the House of Representatives. Shell took oil from Indonesia. Subsequently, we see a huge amount of public money put into fossil infrastructure during the First and Second World War. The military apparatus ran on fossil industry, death and destruction, and supremacist culture.

My climate justice activism was born from the knowledge that militarism and colonialism are the biggest obstacles to an energy transition and a fight against extinction. In 14 years, I have never seen an Iraqi on the stage of the climate march sharing how it feels to endure multiple invasions by the West raining down on them, connecting it to geopolitical interest for resources in the region. In 14 years, I have never seen an Indigenous speaker invited on stage to explain the concept of scorched earth warfare – a term that refers to a game changer in warfare. No longer is war about armed forces fighting each other– the rules of the game change when colonial powers like the U.S. want to depopulate an entire country. There is a license to kill animals so massively that it disrupts Indigenous society. Consider what the Lakota, Dakota and Nakota experienced when fifty million buffalo were slaughtered by the colonial power of what is now the U.S.. With scorched earth warfare, you can issue rewards, calling on citizens to scalp Native women and children and receiving money for it. As was done in the United States. With scorched earth, there is a license for ecocide, for poisoning entire forests with Agent Orange from the air. The US sprayed more than 12 percent of South Vietnam with dioxins from 1961 to 1971, poisoning 10 percent of the country’s farmland and more than 20 percent of its forests. About four million Vietnamese were exposed to much higher concentrations of these dioxins than allowed in the U.S., and three million of them became ill or died. Many more suffered starvation or malnutrition as a result of crop failures. Two generations later, children are still being born with disabilities and deformities because of this scorched earth strategy of the US.

That first climate march I attended was so different from the protests against the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003. There, you felt that lives were really at stake. I thought it was very strange that no connections were made to the geopolitics of oil-related wars. After all, since 1973, oil interests have been the most common reason for military conflict. Nor was the world’s biggest polluter named on stage. When did Greenpeace or Milieudefensie [a Dutch green NGO, red.] ever campaign against the world’s biggest polluter? The U.S. Pentagon pollutes over a hundred nation-states. The Pentagon is the world’s largest institutional user of petroleum—a single military fighter jet, the B-52 Stratofortress, consumes about as much fuel in an hour as the average motorist consumes in 7 years.

At the center of the climate justice struggle waged in 2009 by Bolivian UN Ambassador Pablo Solon was demilitarization, with an agenda for the West to pay their climate debt. This green deal was put together by Indigenous delegations and allies from all over the world at the 2010 World People’s Conference on Climate Change, with about 30,000 participants. Nothing of the sort at the Fossil Free climate demonstration, with mostly bikes and a few bells and whistles. Nothing of the sort at the 2014 climate demonstration, with Freek de Jonge [Dutch comedian, red.], singer Sef and DJ Isis. There was no recognition that Indigenous populations protect 80 percent of the remaining biodiversity, but receive less than one percent of climate funding and have zero representation at the UN negotiating table, where only nation-states participate (and not the populations whose lands are occupied by those nation-states). Currently, $2,200 billion a year is spent on military industry. From that, a lot of the energy transition and climate debt could be financed. But that’s the difference between the climate justice movement and the sustainability movement: one wants to dismantle colonial capitalism, the other just wants to change the plug in the power socket, and problematize fossil fuels.

Yes, but what about the racism of the climate march organization? I’ll admit that in the first few years, I only felt terribly sad every time the organization talked about a so-called march having connected us all, while the knowledge, history and struggles of colonized populations, who have been fighting for hundreds of years for land and water protection, were invariably dismissed as an afterthought, unimportant or less ‘climate’. Behind that lies a lot of racism that deems our lives, knowledge and struggles inferior. At a climate weekend organized by an NGO, I experienced people walking away when I started talking about rights for Mother Earth. They found the frame of a living earth, which gave birth to us and to whom we have responsibilities, too foreign. They weren’t willing to commit themselves to that worldview. But I, as a person of color with Quechua ancestors, was expected to connect with sterile numbers that erased the genocide of Indigenous populations, erased the military terror on communities and ecosystems of other societies, over and over.

In 2017, a tipping point occurred. After eight years of solitude in the white climate bubble, people from grassroots activist groups managed to arrange the nomination of one speaker from their radical anti-capitalist bloc to the podium of the climate march. The honor went to Olave Nduwanje Basabose from Burundi, currently a Dutch feminist, activist, jurist. There is a tendency to ask people to come and speak who are not themselves rooted in the climate movement. This in itself leads to subsequent accusations that they are not sufficiently ‘engaged’, because their starting point is the fight against injustice, which, while linked to climate politics, does not put CO2 emissions at the center. This critique was raised again this year, albeit not internally this time, but in all the newspapers. Sahar, the Afghan anti-war voice, peace prize winner and jurist, is said to have failed. And because the organization of the climate march has committed blunder after blunder against her, the Indigenous people and the Palestine bloc, she is now publicly condemned with the accusation that she did not provide connectedness.

An unrealistic expectation is placed on speakers of color when they step onto the stage at a climate march. They are expected to be able to bridge the gap between communities whose history, knowledge, philosophy of life, life and death are deemed totally irrelevant in relation to CO2 emissions, which should be the central focus. They are expected to be able to generate an image on stage of a broad movement that is ‘diverse’. But I have witnessed people being traumatized by speaking on the climate march stage several times. First of all, by the way they are treated, and secondly, because of the divisive and vehement reactions they receive, and finally because there is zero aftercare. Personally, I have never been asked to be a speaker at a national climate march. That is significant in itself. But I have a long memory of abuses.

Before Olave could step onto to the stage, she was furiously addressed by a climate march organizer from Greenpeace. He was upset that other people from her bloc had walked through the gate of the Rijksmuseum, even though it was not on the route of the demonstration. He seemed unaware that, as a white man with climate-march authority, he disproportionately made the environment unsafe for a black speaker preparing her speech backstage by unloading a wave of anger onto her. This was especially concerning as she, being the first black trans woman at a climate march, was about to take the stage in front of a sea of white people who were unwilling to discuss climate racism. At that moment, I intervened and removed him from the space where Olave was preparing to give her speech. There was never any aftercare or apology. When Olave took the stage, she didn’t hold back and began talking about how, if you are black, GroenLinks [GreenLeft, a Dutch political party, red.] is just GroenRechts [GreenRight, red.]. Her speech was met with an icy silence. Yes, there was some cheering from our small group of radical anti-capitalists but the majority gave her the side-eye, as she had disrupted the supposedly enjoyable climate march by addressing racism in the green bubble. This feedback was never addressed, and Olave never heard from the climate march organization again.

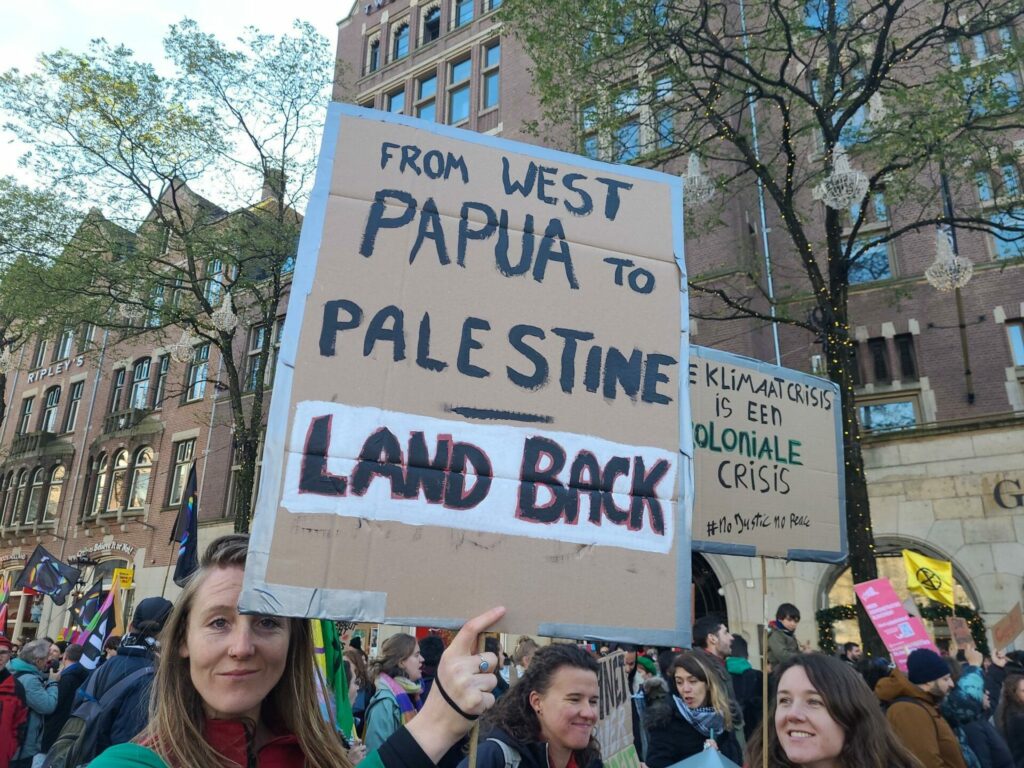

In 2019, an Indigenous voice took the stage for the first time. This voice wasn’t pushed forward by NGO backing but fought its way into the movement like a lion, gaining prominence especially through Nature’s Narrative (a platform for environmentalists of color) and later with Extinction Rebellion. It’s thanks to the fire of Raki Ap from West Papua himself that they could no longer ignore him. And this was not because NGOs understand how the climate crisis originated from colonial policy and how this transformed their way of operating.

At the moment, the climate coalition is evasive in their explanatory statement about the climate march on November 12: “During many of the major climate actions in recent years, activist groups like ‘The Young Papua Collective ism Free West Papua’ have consistently and clearly been able to express the Indigenous perspective against colonialism, capitalism, and racism without the selective outrage we are witnessing now.” They seem to selectively forget that Raki Ap, the spokesperson for Free West Papua NL, was one of the three people who addressed racism in the climate NGO bubble through the media because the organizations were unresponsive in 2019. What had the response been like to the article “Climate movement fails to see activists of color?” [in 2019, red]. Denial, and accusations that their story was not true. The exact same response I have received since 2015 when I increasingly found myself in the same organizing spaces as NGO folks. Time and time again, my work was minimized, ignored, or problematized. And in recent years, I’ve noticed that the tendency to culturally appropriate climate justice is causing new problems. For example, a growing audience is hearing about climate justice with the definition provided by privileged NGOs that mainly focus on climate issues and don’t engage in frontline struggles against evictions and pollution that bring widespread death to the community. They are not accustomed to standing alongside those who are dying and for whom a climate march is a place for political anger, mourning, and protest– not a celebration.

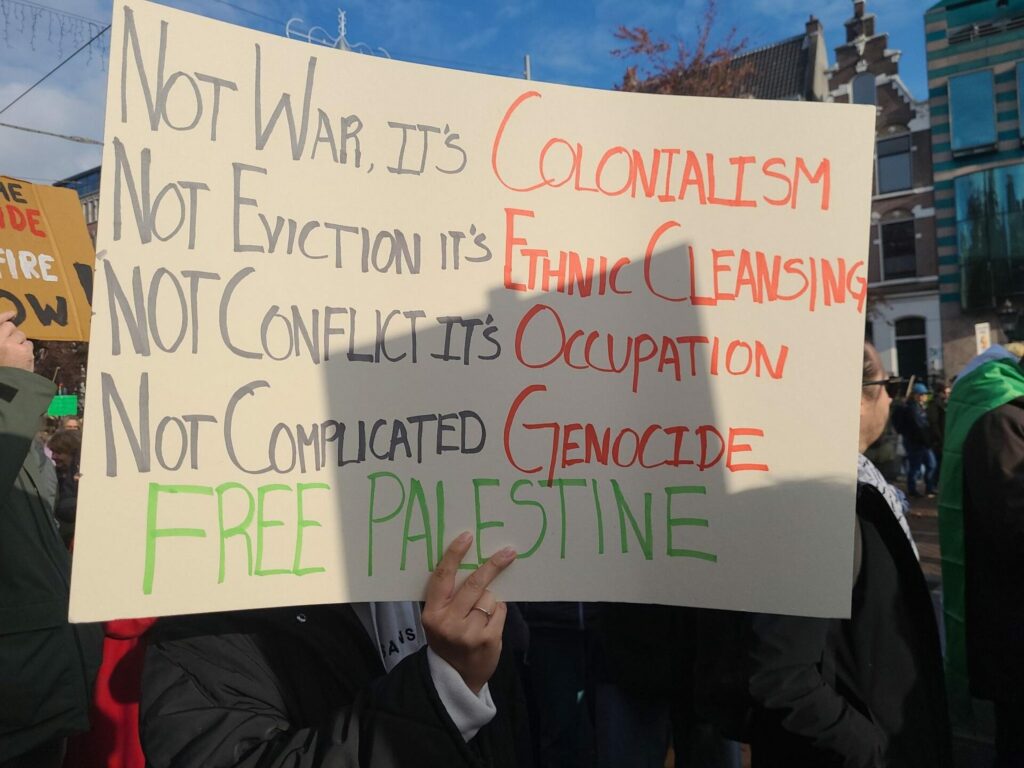

How can the climate coalition post about supposedly listening to Indigenous voices now, while there was an entire battle to have an Indigenous speaker on the stage for this year’s climate march? If they truly understood that Indigenous peoples protect eighty percent of the remaining biodiversity, perhaps they would have committed to dedicating eighty percent of the speaking time on the stage to Indigenous climate justice struggles. Then, they could have learned a lot about Palestine because Indigenous environmental groups like The Red Nation, Indigenous Climate Action, or Indigenous Environmental Network all express solidarity with Palestine through actions, banners, statements, and podcasts. Why? Because they recognize themselves in the genocide taking place there, and recognize that this is scorched-earth colonialism, which was invented with the colonization of the Americas. Driving animals to extinction to destabilize a population is similar to cutting down millions of trees to annex land. Concentration camps and reservations were developed through a political lens of an unbridled sense of superiority. To continue industrial growth at the expense of the sacrificed area can only occur where one fosters a culture of superiority. Capitalists’ profits are deemed more important than the lives of entire populations. The systemic military violence required for all this is a war that cheers for the killing of Indigenous children, just as it is currently a TikTok trend for Israeli individuals to reenact the dehumanizing torture of Palestinians as a joke and then laugh about it.

I conclude with an analysis of what went wrong during the climate march this year. It began with a decision that didn’t take place on stage. Climate Justice for Palestine registered a bloc through the registration form. The coalition’s response was a phone call stating that they wouldn’t include the bloc in the list of blocks on the climate march website. The reasoning was as follows. They didn’t want to see too much solidarity with Palestine. They preferred only one place in the march where, for example, flags would be on display. They kept emphasizing that they wanted the march to be about climate and not Palestine. Additionally, it was suggested that if there were a Palestine bloc, they would also have to allow an Israel bloc. This clearly communicates that they themselves don’t understand the connection between the Indigenous struggle of Palestine for survival and land reclamation and climate. They thus frame Palestine as nationalist and deny a long line of anti-colonial struggle against (water) apartheid, among other things. If the environmental movement would allow a bloc against nuclear weapons, then surely the organization need not allow a pro-nuclear energy bloc, right? With this, the organization indicated that they did not comprehend that ‘there is no two sides to genocide.’ The genocide has been going on since 1948. The environmental movement has had ample time to educate themselves. The climate movement could listen to Naomi Klein– a prominent figure in climate literature and also Jewish– on how Palestine is a climate justice issue.

But the climate march organization would rather discriminate on a sensitive issue, one where Western politics and media are actively contributing to support the genocide. Western media refuse to connect Palestine with the decolonial anti-racism voices in the climate movement. Even when, after thirteen years of activist work, I had succeeded in organizing a whole decolonial anti-racism bloc for the first time for the climate march in Rotterdam last year, with more than twenty partner organizations and groups, and we lobbied through all the climate coalition politics to be allowed to lead the march as the front bloc, we didn’t appear anywhere in the media coverage of the march. Typically, the media capture most images of the front bloc. However, when there’s a banner about ‘white supremacy kills people and planet,’ it is categorically omitted from the media. We also heard from climate march organizers that participants complained about our decolonial anti-racism bloc: they accused us of hijacking the march. The exact same story as this year. Back then, however, they couldn’t mute our microphone because we operated from a position of strength in numbers. And there wasn’t a Greta standing next to us, making the racism of a significant portion of the climate march participants into world news.

By now, the climate march organizers have deliberated amongst themselves in damage-control consultations and issued a statement that lacks clear remorse for the way in which they’ve attempted to silence the decolonial climate justice movement for years now; and every time we conquer a stage or give a workshop their response, steeped in white innocence, is that they find all of it particularly difficult, but that they are mainly concerned with forming connectedness.

When you discriminate against people on whom genocide is carried out, the only connectedness that remains carries an oppressive undertone. There is a double standard at play. On the one hand, the microphone is cut off for people calling for a cease-fire. On the other hand, a politician is given the microphone in a political debate on the climate march stage to proclaim his support for nuclear energy as part of the energy mix we should pursue in The Netherlands. Was his microphone shut off? No. Imagine if a Palestinian had jumped onto the stage and wrested the microphone from the politician’s hands to say that they had come for a climate march, not a political agenda threatening climate and humanity: the nuclear energy lobby is linked to the military lobby for nuclear weapons, and at this moment, Israel is threatening to turn Palestine into a moonscape, with commentators discussing the threat of nuclear weapons that might escalate the war in the region. Would the Palestinian receive the same treatment as the white man with the green jacket? The GreenRight man wasn’t even arrested. Anti-racism activists in the Netherlands have been arrested for wearing a T-shirt with the text “Zwarte Piet is racisme” [“Black Pete is racism”, red.]. But this man was not removed by the climate march organization. Greta’s security at that moment was provided by the activists on the stage. If you express solidarity with decolonial anti-racist climate justice voices, your microphone may be taken away. That is the underlying message of climate march politics, as well as the stage intruder.

And while the media, after the march, primarily spread misinformation about Sahar and Sara, whose microphones were muted, there is no fuss about a politician showing up to endorse nuclear energy on the stage of a so-called climate march. It’s beyond absurd. There is no media outrage over the fact that Sahar received censorship instructions in advance, to speak in place of a Palestinian, addressing multiple conflicts without using the word genocide, and in four minutes, please. There is no reflection on the fact that Indigenous voices were denied a place on the climate march stage, and that artist Shishani gave up her time to the Indigenous Liberation Movement in order to convey a message. There is no reflection about Caribbean climate justice voices not having been given speaking time on the climate march stage. All of this is calculated, decided without us, at the expense of us and the entire climate justice movement. I hope the contours are becoming clear that a tight script is being followed, so that, above all, people don’t get to understand too much about how colonialism has led to the global disruption of ecology and climate. And then, they blame the speakers they’ve asked to be the dye for their diversity picture for being rooted in justice struggles, and solidarity with the movement. How does this climate march organization have a right to exist when they opportunistically allude to the horror of our house being on fire, but don’t provide a podium for those who have lived in that house for decades?

Enough is enough. There have been numerous whistleblowers about the erasure of the decolonial climate justice movement and activists of color in general. From Vanessa Nakate of Uganda to Tonny Nowshin in Germany. From the Wretched of the Earth collective in England to Suzanne Dahliwal. From Meera Ghani in Belgium to myself here in The Netherlands: we have been sounding the alarm for so long. But the climate marchers pulling the strings don’t know what climate justice struggles are. They don’t even know who Chico Mendes is. Chico Mendes was a murdered union leader and environmentalist in Brazil who said, “Ecology without class struggle is gardening”.

A climate march that refuses to stand beside the most oppressed to overturn a culture of supremacy and the militarism that threatens our earth, is not engaged in movement building but distraction. And believe me: we already have plenty of that. Greta was unsafe at the climate march because she stood beside the oppressed. That’s where the struggle for climate justice begins: the willingness to name a shitstorm of injustice and then stand should to shoulder with those who have been fighting for political change longer than you through collective resistance. If you try to silence us, you will never connect with us.

Chihiro Geuzebroek